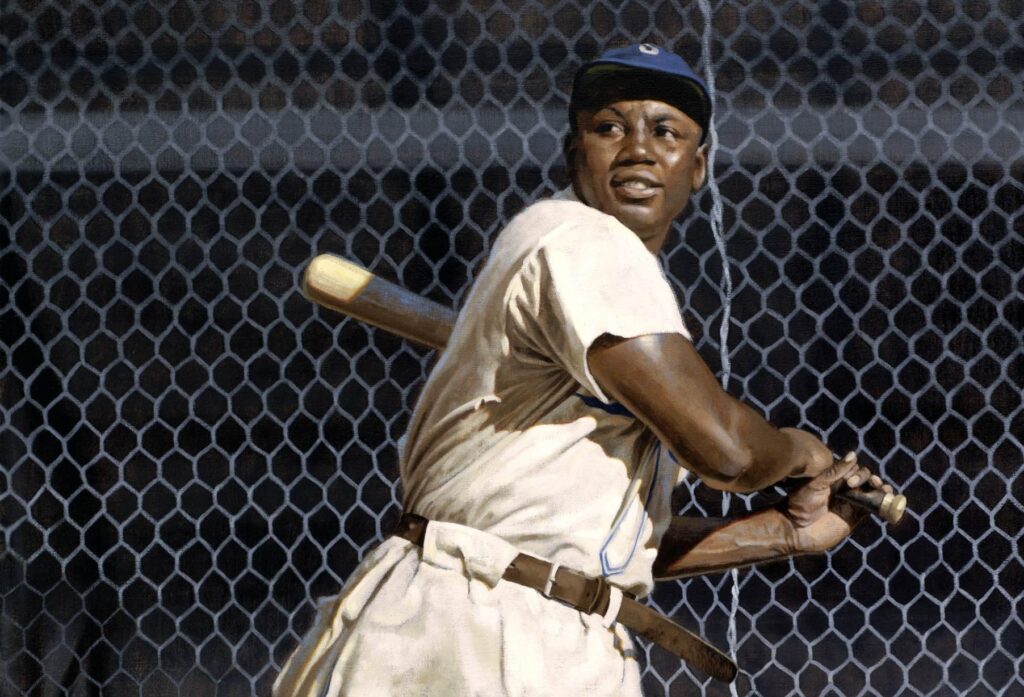

Image credit: Graig Kreindler

Let’s talk about Josh Gibson. A couple of weeks have passed since Gibson officially became the career batting average leader in the history of the major leagues, along with a few other records. Gibson, already a Hall of Famer, played exclusively in the Negro Leagues, a series of leagues that featured Black baseball players in the first half of the twentieth century. There was never an official policy in either the American or National League that teams couldn’t sign Black players, but no one did even though there were obviously talented players available until Jackie Robinson broke the racism line in 1947 with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Gibson didn’t live to see Robinson’s debut.

In 2020, the entity now known as Major League Baseball officially declared that it considered the Negro Leagues to be part of the “major league” heritage of the game. Most of the readers of this article have lived their entire lives in which the American and National Leagues were the only two leagues playing games considered “major.” There have always been other baseball leagues, from affiliated minor ball (the South Atlantic League, the Pacific Coast League, that weird time a couple years ago where they called everything names like A-Southeast and AAA-West) to college leagues to the group of 50-year-olds that plays in the park near my house every week. They are all playing baseball, but they aren’t, y’know, “major.”

We live in a world where it is at once entirely intuitive that the American and National Leagues—which technically don’t even exist anymore—are the only major leagues but also where the only formal declaration that anyone has made on the subject is MLB saying so on their own behalf. But there have been other leagues including the American Association, Union Association, Players’ League, and the Federal League—all of them more than a century gone—which have been given the status of “major leagues” after the fact by MLB, in recognition of the facts that in their time, they were leagues that were on par with the AL and NL.

A couple of weeks ago, MLB officially integrated the statistical record of the Negro Leagues into the “official” record of MLB. The three-and-a-half year delay between the recognition of the Negro Leagues as “major” and moving their numbers into the proper Excel blocks was to allow a statistical review panel to do their work to make sure that they gave the numbers a proper appraisal.

We can’t tell this story without acknowledging the role that racism played in keeping Josh Gibson and other Black players out of the American and National Leagues until 1947. There is no reasonable argument that it was talent that kept Gibson (and others) from playing in the two largest and most famous leagues. It was the color of their skin and only the color of their skin that kept them out. Once the barrier was removed, Black players made their way into both, and some were stars and some were average and some were fringy. For three decades, there were a series of leagues that featured some of the best baseball talent available.

With the welcoming of the Negro Leagues into the major league statistical book, Ty Cobb—who had held the official record for the best career batting average since retiring in 1928 with a .366 mark—suddenly fell to second place behind Gibson’s .372. Critiques of the usefulness of batting average aside, it is still a culturally important measure. For those who grew up with Cobb as their champion, it must have been a little jarring to see someone new at the top of the list, and suddenly, your Uncle Larry who swears that WAR is the work of the devil became very interested in issues like league baselines, sample sizes, and adjusting for the talent pool.

One of the first arguments that came out of the bag was that Gibson’s batting average is based on a much smaller sample of plate appearances than is Cobb’s. Cobb logged more than 13,000 plate appearances over a 24-season career. Gibson’s official stats include only 2,645, even though Gibson played in 14 seasons over the course of 17 years. Surely Cobb should get a few extra points for just stepping into the batter’s box so many more (official) times.

This argument misunderstands how the idea of sample size works. There are a few players in MLB history who have a 1.000 career batting average, but we know that going 1-for-1 doesn’t count. This is a question that I usually get this time of year as fans start to notice players who have made great strides from last year and start to wonder when that performance can be considered something more than a small sample fluke. Over a couple of weeks, a player might go 20-for-50 and mathematically, that’s a .400 batting average, but we will hesitate before we say “That’s a .400 hitter.” When does it become “enough?”

Well, the answer depends on the stat in question, but I will say that by the time you hit 2,000 or so, you’re doing OK. At zero PA, we know nothing about you as a player. Once you get to a few hundred or so, we can feel pretty good about how well your performance reflects your underlying talent. More is technically better, but there’s a diminishing return to it.

We also need to consider that Gibson didn’t come to bat a mere 2,645 times. Gibson came to bat that many times in official league-sanctioned games that we have records for. League play in the Negro Leagues was about 60 games for a season, though Gibson played many more games than that. Teams would play league games that counted in the standings mixed with barnstorming exhibition games that were off the official record. In fact, one reason that Negro League schedules were so short was to accommodate the more profitable barnstorming games. Barnstorming games have traditionally not counted in MLB stats for anyone, and the committee reviewing the Negro League stats have stuck to that here. The committee also required that there be some sort of documentation of the game, and despite our vast record of American and National League games, Negro League games weren’t as well cataloged. What we have then is a subsample of 2,645 plate appearances from Josh Gibson, likely from among a corpus of work that was several times bigger.

To put it another way, if I took a random sample of 2,645 of Ty Cobb’s plate appearances, I feel very confident that I would get something very close to Cobb’s career .366 batting average in that sampling. The math behind it is that we can compare how well similarly suited pairs of 100, then 200, then 500, then 2,645 plate appearances correlate with each other. As the sample size goes up, so does the correlation. One “line in the sand” that’s used in other areas of research is a correlation of .70. Since this is correlating two samples from within the same person (a “split-half” method) then we say that 49 percent of the variation (almost half) is “endogenous.” In other words, we believe that the majority of the performance is explained by the talent of the player. At 2,645, we are way past a split-half correlation of .70.

Which brings us to the second most common objection. Gibson may have hit .372, but what was the quality of the competition? It’s an oddity because people rarely ask that question about the American and National Leagues. It is true that in the Negro Leagues, Gibson played against the best Black players of the day, but then as now, African-Americans made up about 10-12 percent of the United States population. If, for some reason, MLB were to restrict itself to 10 percent of the population in the United States, the MLB players from that 10 percent would still be in the Majors and then you’d find the Triple-A and Double-A players who were eligible, meaning that those current MLB players would be facing off against lower level players and could pad their stats that way. Cobb faced a league in which the best Black players were excluded as well.

I understand the argument, but it’s rather disingenuous to bring it up now. The size and scope of the talent pool in MLB has changed plenty over the years, both because the number of teams has expanded, but also because of changes (mostly increases) in population, but also the internationalization of the game and the opening of new roles to new types of players. There’s also been an increase in salaries, drawing more athletes into the game, rather than working on the farm, but there’s also been competition from other sports that’s grown up. And yet, we don’t sit around agonizing over whether modern competition has robbed some recent player of a chance at the record books. We functionally ignore it. A player might have had a better chance of breaking a record in a different era, but it’s on them for not having been born earlier.

The reality was that Josh Gibson didn’t refuse to play in the National or American Leagues as a choice. It was a choice made for Gibson and all the Negro League players. Had the racism line not been there the whole time, talent would have spread out differently. Clearly, there was enough fan interest to support the AL, NL, and a series of Negro Leagues. It’s possible that we would have seen talent diffuse among the three leagues, all of whom would have ended up with some of the top, middle, and bottom of the talent ladder. We will never know.

I appreciate that everyone wants everything to be nice and tidy, and I think that’s where a lot of the debate around the Negro Leagues has come from. There are now two undisputed major leagues who play a standard schedule every year and we have impeccable record keeping and thankfully, there is no more racism line. In that sort of world, we would have record books that didn’t need much debate.

The problem of the 1920s through the 1940s was that things weren’t nice and tidy. There was a racism line and there were players who were kept out of the record books because of it. Josh Gibson was one of them. We are left with the options of either dealing with the mess or ignoring it, and I believe MLB has chosen correctly.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.