Hello, prospective broadcaster with luminous, thick hair. We’re reaching out to you because you expressed some trepidation over the seemingly impossible task of improvising everything within a three-hour baseball game, while stand up comics are thrilled to scrape together 30 minutes of material. We understand! It is impossible. But to allay your concerns, we’re supplying a recent example of a Broadcasting Situation, in the hope that it can provide an example of how to turn any baseball occurrence into a teachable moment. Enjoy!

The setting: A Giants game. As an announcer, the demands of the job are both straightforward (narrate the game) and expansive (be consistently interesting for basically every day for six-plus months). However, the specific knowledge required in the booth—whether as a play-by-play announcer or color commentator—is largely limited to baseball-relevant information. Even that directive is blindered; though many announcers have grown increasingly more knowledgeable of and willing to deploy advanced analytical stats in game, plenty of the game’s famous voices have gotten by fine and continue to with only the standard baseball announcer’s toolbox. Mix them in with a mild awareness of the news and pop culture, familiarity with the cities one announces for and visits, how well each batter has done against each pitcher in their six career head-to-head plate appearances, and some personal quirks, and your average announcer is set. What more could you need?

Well, here’s a case study: A rarely used implement within the announcer’s kit is birding knowledge—sure, you might see the odd pigeon at the ballpark, or the occasional seagull in coastal venues, but there are few birders at the average game looking to log their latest ID. While most announcers presumably have rich inner lives, the contingent who hold active memberships in the National Audubon Society is likely small (and as we learned from Matt Sussman’s attempts to rechristen the “group Maddux,” perhaps there’s little virtue in supporting a society that retained the name of a man who “did despicable things even by the standards of his day.”) So between those, you felt pretty well justified in keeping your knowledge of class Aves to the purely appreciative: “Cool bird!” And now, perspective announcer, put yourself in the shoes of two seasoned broadcasters. How’d it turn out for them?

On Saturday afternoon, the Reds took on the Giants in San Francisco, with the game nationally televised on Fox and called by play-by-play announcer Eric Karros and color commentator Jason Benetti. The latter voice, now with the Tigers, is known for his acumen with the analytical side of the sport, appearing on “Statcast broadcasts” several times in the final few seasons of his White Sox tenure (2016-23) and recently discussing run expectancy matrices on air. The availability of that mode doesn’t mean Benetti is freed from the rails of topical conversation, however. Take this exchange in the top of the fourth (interestingly the first available frame from the contest, possibly due to apparent technical issues):

KARROS: “Do you have any tattoos?”

BENETTI: “I don’t.”

KARROS: “Mason Black does.”

BENETTI: “Ohh no.”

[Further conversation is forestalled by the third out and cut to commercial]

Sometimes it goes like that. Other discussions linger.

“There’s a bird in short left center who’s suddenly become a star,” notes Benetti. “That’s not just a bird,” responds Karros, “that’s a, that’s a big ahh bird.” To Benetti’s inquiry as to whether the avian is a crane, Karros says, “I don’t know what it is … When you say bird, I think like somebody just flying in, swooping, getting out of there.” So we know he’s heard of them. An apparently less settled concern is whether either of the pair has heard of pelicans.

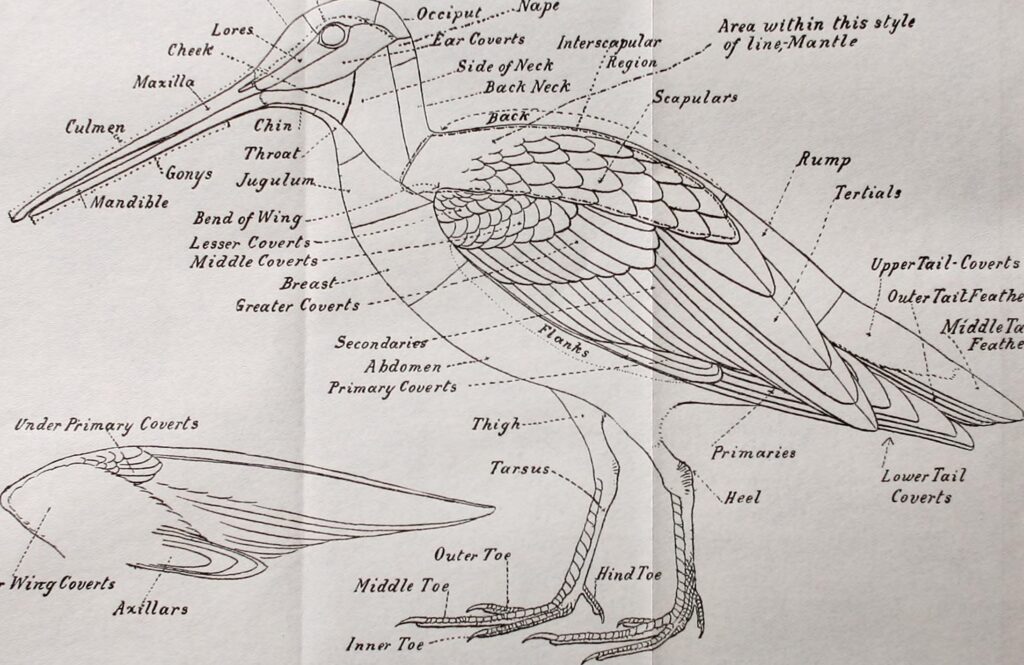

Pelicans are large birds, as Karros astutely discerns. The Brown Pelican, an example of which emerged Saturday, has an average wingspan of around 7-foot-6, shy of their cousins the white pelicans and well short of the 10-foot spans (largest among extant birds) Andean Condors commonly achieve, but substantially larger than the Sandhill Crane (6-foot-8). Whooping Cranes tend to be nearly of a size with Brown Pelicans, but are not typically found anywhere near the San Francisco area. In terms of coloration, the adult Sandhill Crane is typically observed as “all gray with red patch on head” and has a distinctive feature of a “bushy tuft of feathers on rump.” The Brown Pelican is “brown-gray with pale head.” That’s not exactly of a piece with the other bird, but it’s an understandable mistake. Less so is a feature the Audubon society does not attempt to describe any further than “distinctive shape.” Let’s play the game show that’s taking intrepid announcers across the nation by storm, Spot the Pelican!

How’d you do? Don’t worry, we know it’s hard—that’s why we’re making available for purchase this simple course, for only four easy payments of $79.99 plus S&H! There will be another chance later on. For now, we’ll zoom and enhance on that beak—you’ll want to remember this!

Variously referring to the pelican as “the bird,” “my man right out there,” a “video bird,” and “effortless, fluid, and graceful,” our announcers speculate no further about the potential species that confronts them. The question hangs heavy in the air. The creature (a Brown Pelican) soon takes off, the path of its widening gyre slackening Karros and Benetti’s hold on the center of the baseball universe. The big bird could no more have unmoored our protagonists than if an elusive relative of the Big Bird himself landed on the field in its nine-feet-tall glory. Displaying a lack of knowledge so publicly is an acknowledgment the project of self-realization is never complete, the sort of minor existential unmooring to which growing up requires becoming accustomed—one whose effects you’ll have to take delicate care to sidestep in the broadcast booth, as observed.

As the bird flies away, it largely exits the conversation between our commentary duo. This is typically a mistake: Wring that bird (not literally) for every ounce of material it can possibly offer; otherwise you may have to talk about Nick Ahmed! When the topic at hand is so far above an announcer’s head (literally), though, perhaps anyone might be inspired to discuss the minutiae of defensive metrics. The bird’s departure is likened to a home run trot, a grasping attempt to re-establish common ground betwixt a team clearly fearful that the bird has robbed them of their binding tissue in some avicular Tower of Babel situation. Mason Black exits with two outs in the top of the fifth, the Reds are retired and the bottom of the frame passes without mention of the fracture in the spoken universe. Randy Johnson’s name comes up as Thairo Estrada bats—now, announcers, this is a no-no as far as bird avoidance goes—but note how Benetti and Karros nimbly dodge the birdseed bullet, running out the string on the anecdote like two same-sex roommates in the sixties bravely enduring the latest spiel about someone who would be “perfect” for one of them.

In the top of the sixth Benetti and Karros return chastened, noting “Twitter is really good for ornithology.” Understanding the vital and terrible influence that social media has on the world of broadcasters is a key to success. Remember, Twitter followers are like customers, in that they are always right, and they are also always mad. Our heroes take the position that they didn’t have a clear view of the, again, seven and a half-foot wingspan, four-and-a-half foot tall Brown Pelican. This is not so bad a strategy as avoidance goes—better than “I oppose the taxonomic system of classification and thus reject the name of Brown Pelican,” worse than “my best friend when I was growing up was a Sandhill Crane, and she looked just like that—I swear, I’ll bring in pictures tomorrow, Beverly Cleary A Crane sure as hell knew what kind of bird she was and you’re disrespecting our friendship and her noble sacrifice by saying that was definitely a Brown Pelican.” But the guys in our sponsored example did okay—they got past the moment, reconciled the distinctively beak-shaped rift in the universe. The bird took control of the fans, but not Benetti and Karros’ audial authority over the game. That’s something that can only be given away.

“Mother Nature is always victorious,” but on Saturday so were Misters Karros and Benetti, over that selfsame entropy. Take time to study this episode, watching this (partially preserved) game in full four or even seven (not six) times if necessary, muting the feed and substituting your own dialogue as practice. Use different voices if this is a helpful tool, and try wielding various metaphors for the pelican to get through some seven-pitch at-bats. Pelicans are symbols of caring and self-sacrifice, and can also represent purity to some cultures. They also can carry an amazing number of diseases and parasites—an endless array of fecund possibility. When you think of it, baseball can be terrifyingly infinite, too! This fear is tackled in the second course, with special guest lecturer AI Zeno, again available for a reasonable price.

Just one more thing: What is this?

If you still missed that one, you might just not be cut out for identifying Brown Pelicans. That’s okay, though—you can always pepper in some theatre references instead! “Bye bye, birdie.”

To Jason Benetti and/or Eric Karros: I tried my very best to not mix up your voices. Sorry if I did anyway/for this dumb, dumb piece. To everyone else: I just have, like, so much trouble distinguishing between men’s voices, sorry!

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.