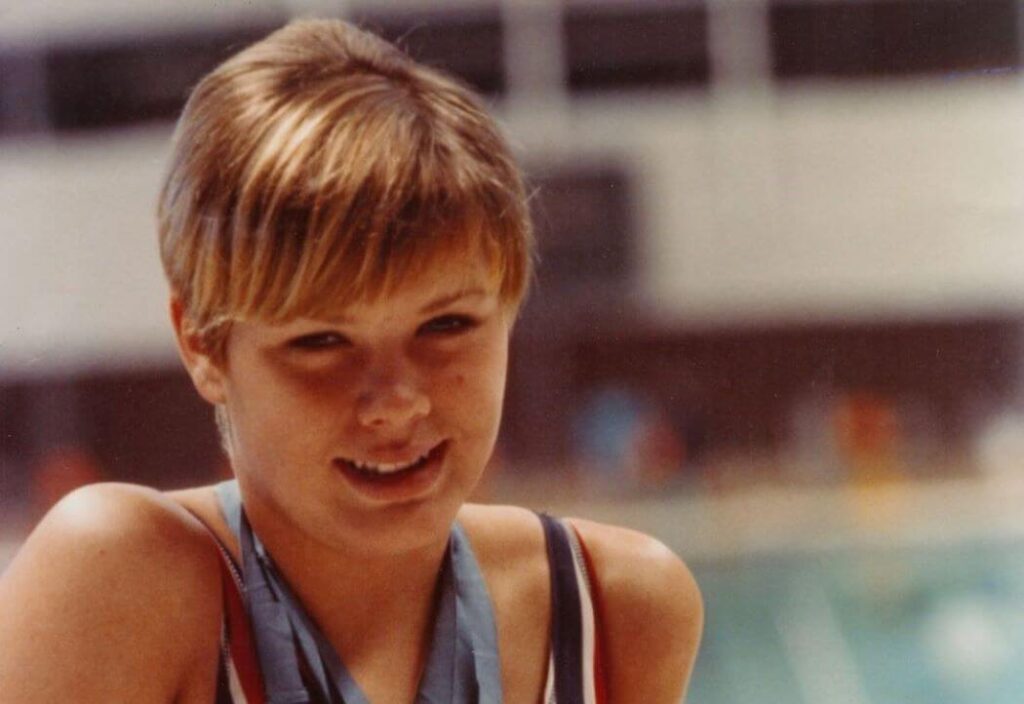

Celebrating the Olympic Trifecta of Debbie Meyer At the 1968 Mexico City Games

This week marks the 56th anniversary of the start of the 1968 Olympics Games in Mexico City. At those Games, Debbie Meyer completed her freestyle triple, winning gold in the 200, 400 and 800 distances. It was a feat that went unmatched until the 2016 Games in Rio de Janeiro, when Katie Ledecky pulled off the feat.

Today, we celebrate Meyer’s greatness.

A study of the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City typically produces three standout moments. There was the effect of altitude, which at more than 7,000 feet contributed to breathing and endurance issues for the athlete. There was the political statement made by Tommie Smith and John Carlos during the medal ceremony for the 200-meter dash, the track athletes raising black-gloved fists to raise awareness of human rights, particularly those of the black race. There was the flight of Bob Beamon, whose long jump of more than 29 feet broke the world record by nearly two feet and endured as the global standard for more than two decades.

Overshadowed in Mexico City was the story of a teenage girl who achieved a feat in the pool which had never before been accomplished, and went unmatched until the excellence of Katie Ledecky in Rio de Janeiro. No, Debbie Meyer did not receive the same attention as the elevation of the host city or the same hype as members of the American track and field squad. Those in swimming circles, however, have a deep appreciation for Meyer, considered a legend in the distance events.

By the time she was a 14-year-old, Meyer was a major factor on the international scene. She had broken world records in the 400 freestyle, 800 freestyle and 1500 freestyle and the buzz concerning her talent couldn’t be slowed. As the latest in a long line of young girls to emerge as aquatic superstars, Meyer was viewed as a leading hope for American success at the 1968 Games. Those expectations only grew when Meyer won a pair of gold medals at the 1967 Pan American Games and continued to break world records.

Still, it’s one thing to be surrounded by hype and quite another to perform under the pressure. For Meyer, there was never a sign of strain linked to the lofty predictions attached to her name. She simply went about her business, as a fun-loving teenager and star athlete. At the 1968 Olympic Trials, Meyer set world records in the 200 freestyle, 400 freestyle and 800 freestyle, making her an overwhelming favorite to prevail in Mexico City.

Trained by Sherm Chavoor at the Arden Hills Swim Club in California, Meyer had a happy-go-lucky demeanor about her, a personality which was highlighted in numerous newspaper and magazine articles, including a Sports Illustrated profile. Sure, Meyer was aware of her status as a world-record holder and the woman to beat at the 1968 Games, but she handled her position with aplomb.

“There are a lot of girls who’d love to beat me,” she said. “That puts pressure on me. But I just try to stay calm and set goals for myself.”

The emergence of Meyer as a star coincided with a favorable change for the youngster in the Olympic swimming schedule. The 1968 Games marked the first time the 200 freestyle and 800 freestyle were part of the women’s program, consequently providing Meyer with an opportunity to showcase her range. Prior to 1968, female swimmers were limited to the 100 freestyle and 400 freestyle, a minimized schedule which surely denied a few of Meyer’s predecessors – Martha Norelius, Helene Madison, Lorraine Crapp and Dawn Fraser, in particular – the chance to bolster their gold-medal totals.

Photo Courtesy: Debbie Meyer

A 16-year-old student at Rio Americano High School in Sacramento, California when the 1968 Games were held, Meyer may have found the high altitude of Mexico City as an advantage. As an asthmatic, Meyer was familiar with enduring practices or races with breathing problems. In the thin air of Mexico City, her rivals came to understand how difficult it can be to compete in top form when oxygen debt is a factor.

Regardless of the conditions, Meyer was a focal point from the start. She opened with a convincing victory in the 400 freestyle in 4:31.8, almost four seconds clear of her American teammate Linda Gustavson. Meyer then followed with a half-second triumph over fellow American Jan Henne in the 200 freestyle, a win which set the stage for a run at history.

But before Meyer got the chance to contest the 800 freestyle and become the first individual – male or female – to win a gold medal in three freestyle events at the same Olympics, she was hit hard by a stomach bug. For a few days, Meyer was in bad shape, a case of Montezuma’s Revenge keeping Meyer close to a bathroom. But she was not going to miss the 800 freestyle due to illness and went to work in less-than-prime condition.

After winning her preliminary of the 800 freestyle, Meyer turned up the pace in the championship final, recording a winning time of 9:24.0, more than 11 seconds quicker than silver medalist Pam Kruse of the United States.

“I still get goose bumps when I think about it,” Chavoor said. “She was a hell of an athlete. She was in a class by herself.”

In less than a week, Meyer made history and was viewed as the queen of her sport. Had she come along in a different era, Meyer could have cashed in on her fame. Nonetheless, she was pleased with what she achieved.

“I wasn’t into it for the monetary reasons,” she said. “I was interested in swimming, working out, traveling, making friends and setting challenges.”

Following her Olympic excellence, Meyer returned to training, her sights set on pursuing additional gold medals at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. With world records in the 400 freestyle and 1500 freestyle following her exploits in Mexico City, there was reason to believe Meyer had the ability to add to her medal collection, even if Australia’s Shane Gould was a fast-rising star.

But at the beginning of 1972, Meyer decided she was done. She didn’t possess the same passion and desire which catapulted her to unprecedented success in 1968. Whether she would have enhanced her Olympic portfolio will remain a mystery, although it was clear she had improved since her first Olympic foray.

“At first I wanted to repeat in the 200, 400 and 800,” she said. “But I made up my mind to quit on Jan. 8, 1972. The practices weren’t fun anymore and had become drudgery. I knew the time had come for me to hang up my suit. My times were still competitive, but I can’t say how I might have done. There was a lot more competition in 1972. East Germany was just picking up and there was Shane Gould from Australia.”

Photo Courtesy: ISHOF

In assessing her chances at the 1972 Games, Meyer took the humble route. Chavoor, who coached Mark Spitz to seven gold medals in Munich, had a different viewpoint. He did, however, understand Meyer’s reasoning for walking away.

“She would have won,” Chavoor said. “But the motivation was gone. At 16, she had hit the highest peak of any swimmer ever. She had reached the top.”

The achievements from Meyer’s career are numerous. In addition to her Olympic trifecta, she established a total of 15 world records over four events and became the first woman to break the 18-minute barrier in the 1500 freestyle. In 1968, she became the youngest winner of the James E. Sullivan Award, annually presented to the premier amateur athlete in the United States, and in 1977, she was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame.

“I don’t think there’s any one thing (which stands out about my career). I think just the total package,” Meyer said. “I loved every minute of it, even the days when I hated working out. I’ve had great memories. I just hope I can keep them fresh.”